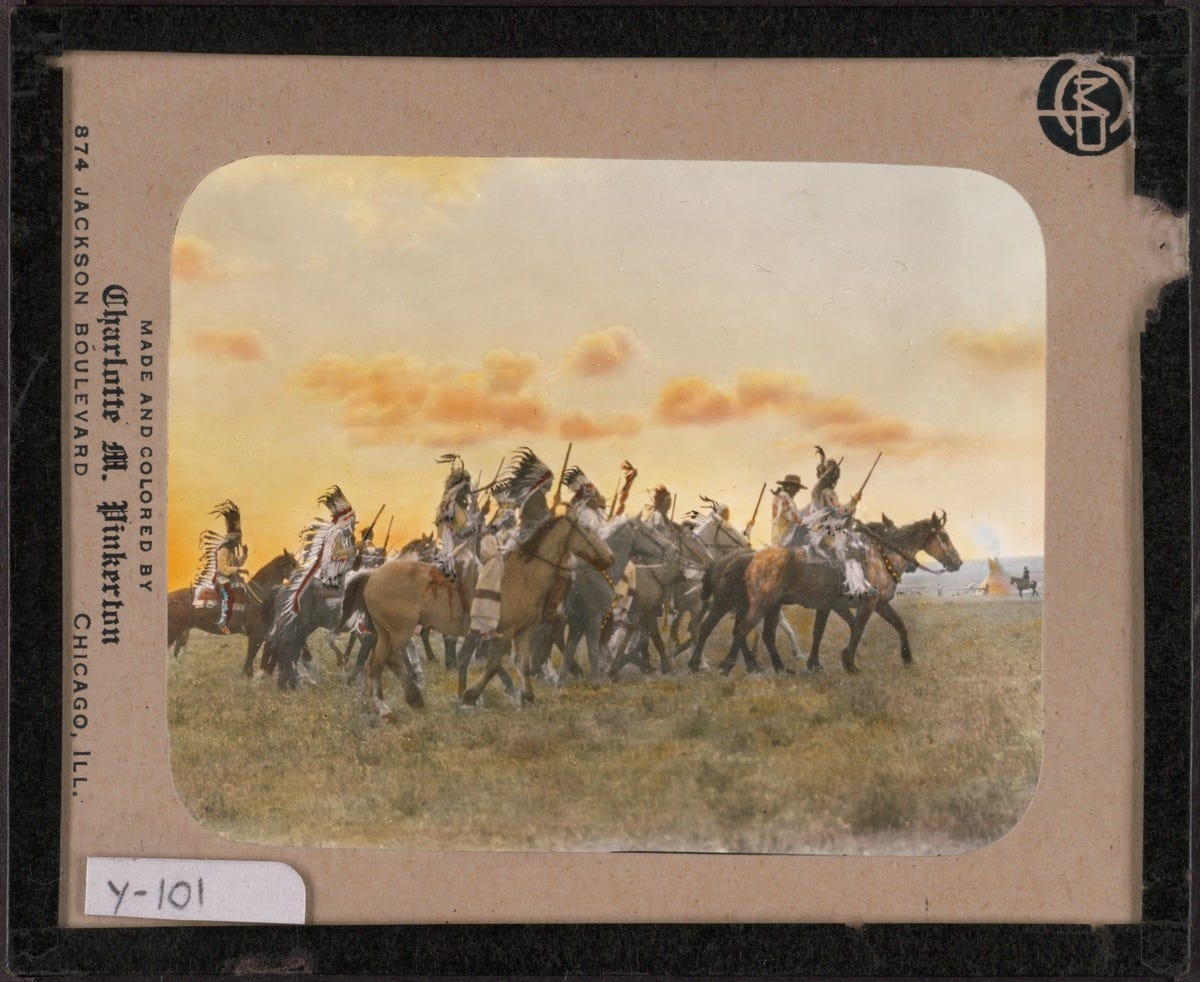

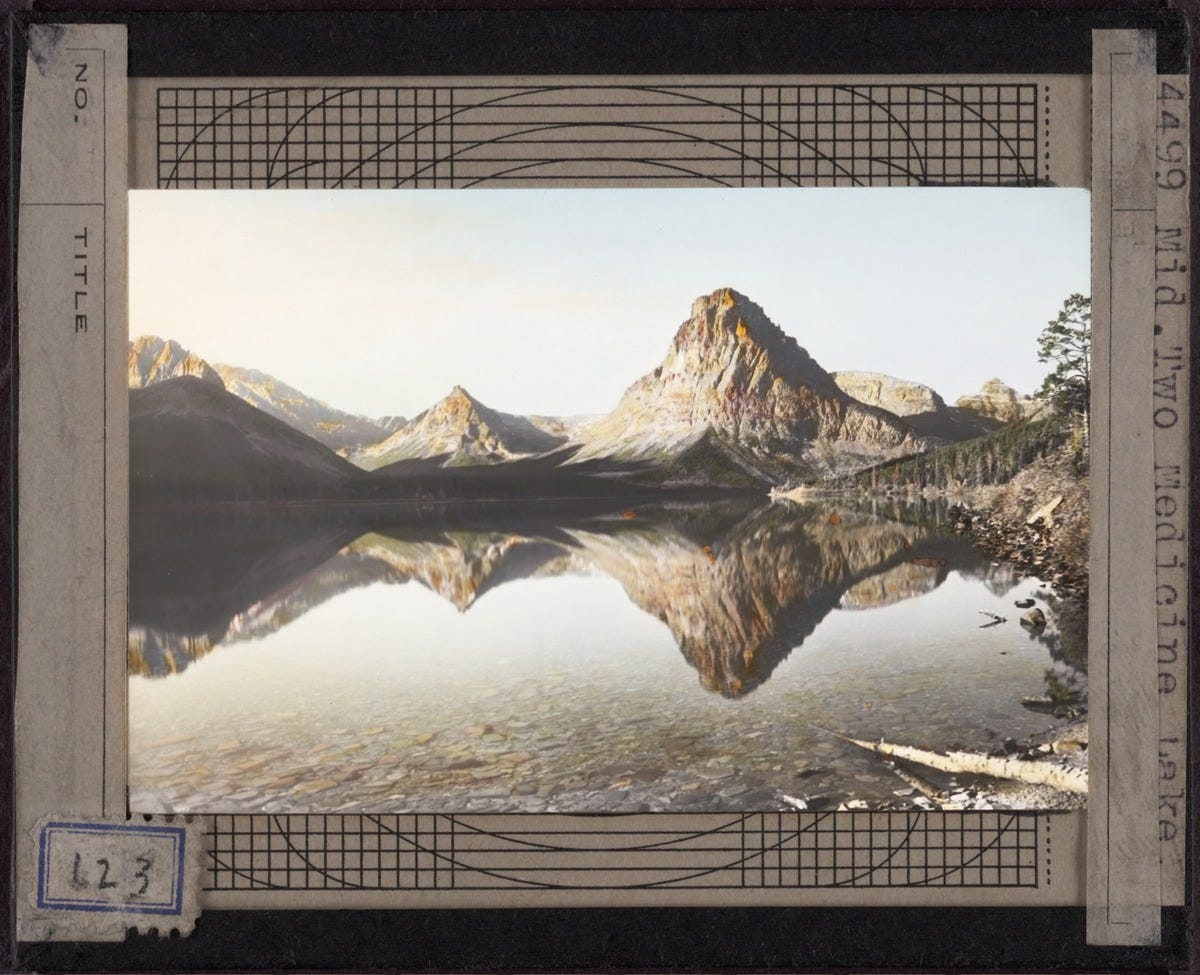

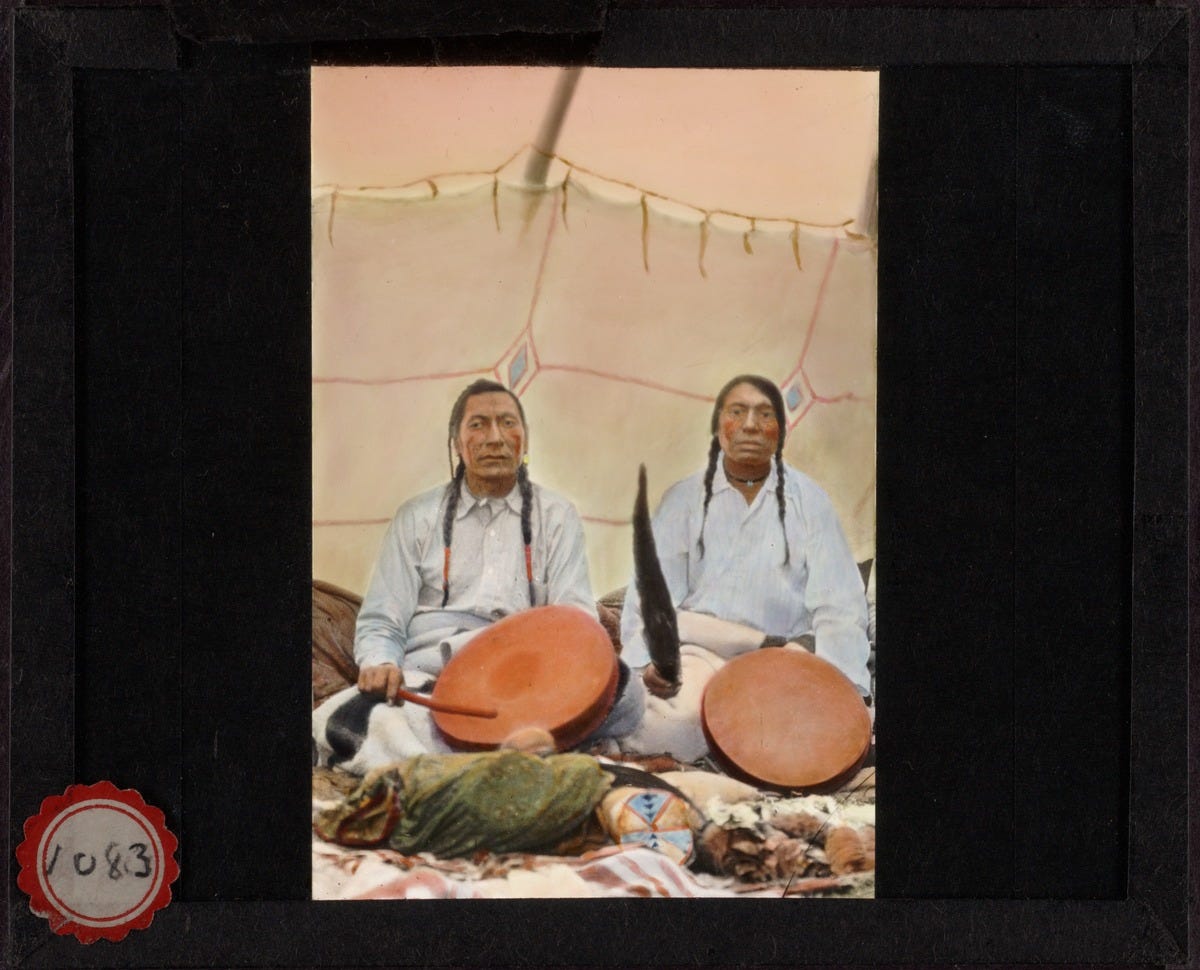

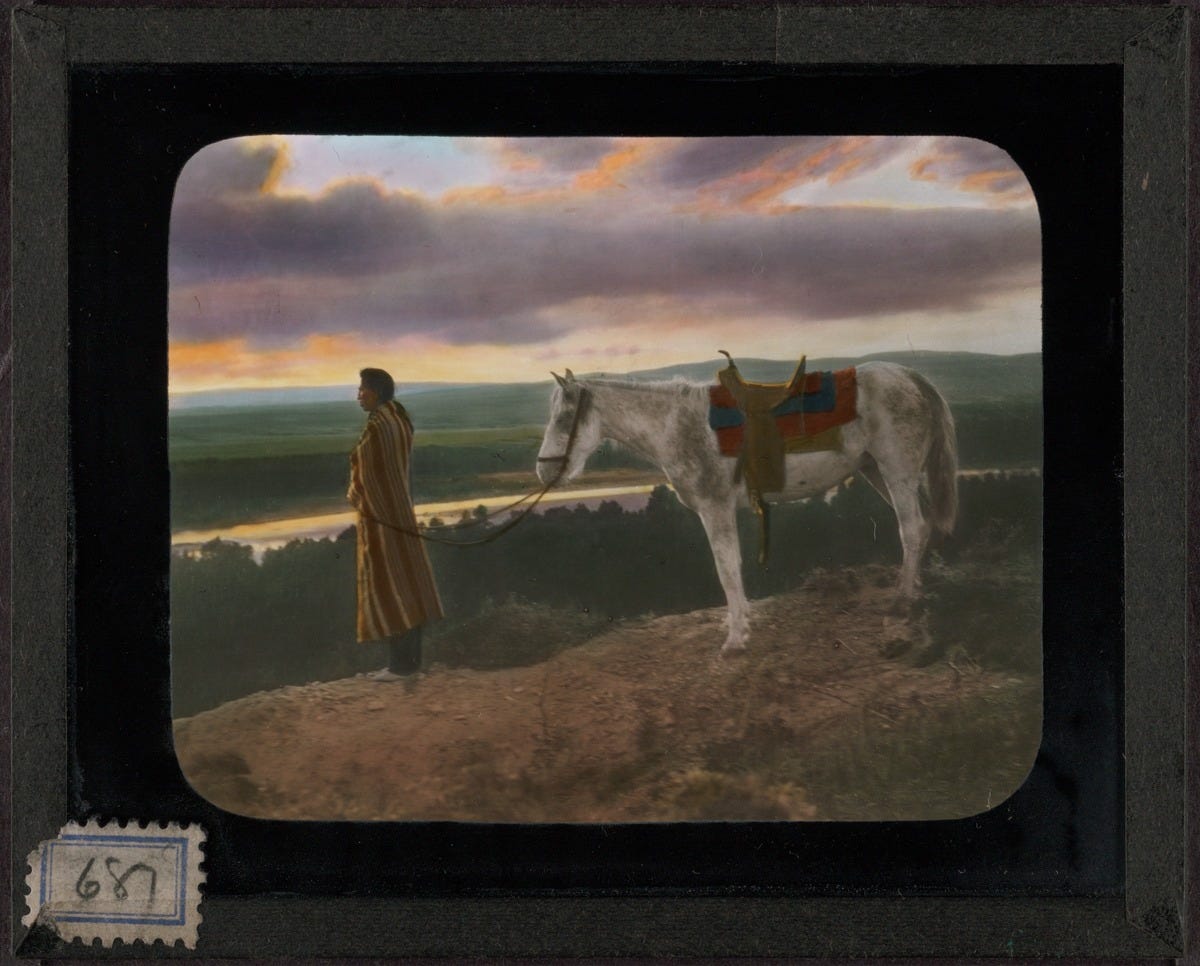

Early photos of the Blackfoot tribe show a beautifully idealized version of life on the plains

Typhoid fever changed Walter McClintock’s life. In 1895, the stricken Yale University graduate sought rest and recuperation at a North Dakota dude ranch and found himself drawn to the open expanse of the Great Plains. The following year, he joined a forestry expedition as a photographer and went west once again. This time it was the Blackfoot people who captured his imagination; when the expedition parted ways McClintock ingratiated himself with a nearby community, bought a lodge, and took a lot of photographs.

Using a magic lantern, these hand-painted glass plates projected soft, dreamy landscapes for audiences across America and Europe. McClintock began photographing the Blackfoot people as a means of preserving what he feared were their rapidly dying traditions. In doing so he captured his own fantasies of a world long dead. Indigenous tribes had already been driven onto reservations when these pictures were made. Bison had been driven to the brink of extinction, children were being forced into boarding schools, and the government was cracking down on religious rites and communal lands. McClintock just chose to frame his images around the poverty, the deprivations, and any hint of modern life. The idyllic Montana conjured up by these slides was preferable to the surrounding reality, not to mention the humdrum reality of the family carpet business waiting back in Pittsburgh.

McClintock began donating portions of his collection to institutions in the 1920s, including his alma mater, where he secured a recurring speaking engagement. It was a wise move, as glass plates were fading in the light of new technology. Film manufacturers were making great strides developing new processes, and in 1935 Eastman Kodak released Kodachrome, ushering in an era of accessible color photography.

No comments:

Post a Comment