it’s a day all Americans know changed the course of our daily

lives in US

The military has been monitoring the skies over the U.S. ever

since

“Our computer systems are bigger and better. … You should see all of the radars that are now hooked up. Everything the FAA sees, we see. We are much more actively involved in the identification of all aircraft in the United States,”

In NORAD personnal words: Maintain your vigilance. Maintain your professionalism. We’re here for a reason. We’ve evolved over the last 10 years to develop into an air defense organization that has a job not only in defending from attacks from the outside, but also for defending asymmetric threats like we – that occurred on 9/11. Just maintain your professionalism and I think everything will work out

The attacks on 9/11, that was a slap. That was a slap to us

__________

USDOD

It’s been 17 years since Sept. 11, when terrorists hijacked four

commercial airliners and flew them into New York’s iconic World Trade Center,

the Pentagon and a field in rural western Pennsylvania, killing nearly 3,000

U.S. citizens.

Whether the events of that day were etched in your memory

forever, or you were too young to understand it at the time, it’s a day all

Americans know changed the course of our daily lives.

New York Air National Guard Maj. Jeremy Powell was a 31-year-old tech

sergeant taking part in Exercise Vigilant Guardian when 9/11 occurred. He was

the first military person to learn about the hijackings, having taken the

initial call from the Federal Aviation Administration’s Boston center.

Master

Sgt. Stacia Rountree was a 23-year-old senior airman working as an

identification technician. Vigilant Guardian was her first major NORAD

exercise.

Like everyone else, Powell and Rountree remember that day

vividly. Here are some of the things I learned from them. Who knows – these

facts might be new to you, too.

There was a lot of initial confusion.

It took some time for NEADS (North East Air Defense Sector, now

Eastern Air Defense Sector) ) to realize 9/11 was a real-world scenario and not

part of the exercise. Once they did, there was even more confusion trying to

find the missing planes, which always seemed to be a step ahead of them.

“We were treating all the information we got as real-time, not

understanding that it was coming to us late,” said Rountree, who basically

became a liaison between the FAA and the military for the rest of that day.

“We were trying to figure out departure destination, how many

people were on board, how big the aircraft actually was, and factoring all of

that stuff in. That way the [F-15 and F-16] fighters, when they got airborne,

would know that they had the right plane in sight,” she said.

”I stayed on the phone for 12-14 hours, just calling all the

bases and asking how quick the fighters could get armed, get airborne, and if

they could go to a certain location,” Powell said.

There wasn’t much time between the first FAA call and the first

crash.

Just 10 minutes elapsed between the time Powell took the first

call to NEADS about the hijackings to when the first plane, American Airlines

Flight 11, hit the North Tower – not enough time to get fighters into the air.

According to the 9/11 Commission’s report, the call from the

FAA’s Boston center came into NEADS at 8:37 a.m.

“8:46 is when I scrambled the first fighters [from Otis Air

National Guard Base, Massachusetts], and then 8:53 they were airborne,” Powell

said.

But it was too late to help American 11, which hit the World

Trade Center’s North Tower at 8:47 a.m.

There were several more reports of hijackings that day.

By the time the day was over, Rountree said there were probably

19 or 20 planes that she and the other ID techs had investigating as possible

hijackings. Only the initial four – American 11, United Airlines Flight 175,

American Airlines Flight 77 and United Airlines Flight 93 – were the real deal.

At one point, there were reports that American 11 was still

airborne. Air traffic controllers likely confused it with American 77, which

was somewhere over Washington, D.C., air-space. Rountree said she tried to

contact the FAA’s Washington Center to get a position on it, while Langley Air

Force Base fighters were trying to get to the capital.

“It was probably only a couple of minutes, but to me, it seemed

like a lifetime. Then we got the reports that the plane hit the Pentagon,”

Rountree remembered. “I was actively trying to find that plane, and I felt that

we may have had some time. We didn’t.”

There had been discussions of fighter pilots making the ultimate

sacrifice.

The fighters were meant only to shadow potentially hijacked

planes, but Rountree said there was discussion of those pilots making the

ultimate sacrifice.

“In case their weapons were out, and if we would have had to use

force, they were discussing whether or not those guys would have to go

kamikaze,” she said, meaning some pilots were considering risking their own

lives by using their planes to stop hijacked jetliners. “It was scary, when you

thought about the possibility of them having to do that.”

There was a heartbreaking feeling of hope for Flight

93.

While all of the crashes were shocking, Rountree said that, for

her, United 93 was the saddest. They had been trying to find the plane on radar

and had called the FAA to get an updated position.

“They said, ‘It’s down,’ and we were thinking it landed,”

Rountree remembered. But when they asked for landing confirmation, the info was

clarified – it crashed. “For us, you had that glimmer of hope, and then… .”

NEADS was evacuated on Sept. 12 thanks to an unknown aircraft.

The day after 9/11, NEADS was evacuated because there was an

unknown plane up at the time, and no one was supposed to be airborne.

“There were fighters coming back from air patrol over NYC … so

our commander had them go supersonic over to where we were so they could figure

out what it was. They thought it was heading toward us,” Rountree said.

It turned out to be a harmless floatplane, and it was forced to

land.

9/11 changed the role of the air defense sectors.

“Back then, the primary focus was that we were looking out at

people coming to attack us from the outside,” Powell said. “We weren’t really

focused on the inside.”

“Nobody thought that somebody would go ahead and utilize planes

that were in the U.S. to do something, so our radar coverage was indicative of

that,” Rountree explained.

“Now, our coverage has definitely increased. It’s night and day

versus then.”

The sector now has new and evolving technology.

“Our computer systems are bigger and better. … You should see

all of the radars that are now hooked up. Everything the FAA sees, we see. We

are much more actively involved in the identification of all aircraft in the

United States,” Powell said.

Before 9/11, Rountree said they couldn’t always get in touch

with critical personnel at the FAA centers. Now they can.

“We really didn’t have to talk to the various Air Traffic

Control Center supervisors. Now, we have instant lines with everybody,” she

said.

The military has been monitoring the skies over the U.S. ever

since.

“A lot of people didn’t even realize that we were probably

there, or what we even do, which could be a good thing,” Powell said. “It

reinforces the idea that somebody’s always watching you, especially in the sky.

The FAA’s there – that is their airspace – but the military is, too.”

Never Forget

__________

9/11 COMMISSION REPORT

Of the many unanswered questions about the attacks of September

11, one of the most important is: Why were none of the four planes

intercepted? A rough answer is that the failure of the US air defenses

can be traced to a number of factors and people. There were policy

changes, facility changes, and personnel changes that had recently been made,

and there were highly coincidental military exercises that were occurring on

that day. But some of the most startling facts about the air defense

failures have to do with the utter failure of communications between the agencies

responsible for protecting the nation. At the Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA), two people stood out in this failed chain of

communications. One was a lawyer on his first day at the job, and another

was a Special Operations Commander who was never held responsible for his

critical role, or even questioned about it.

The 9/11 Commission wrote in its report that “On 9/11, the

defense of U.S. airspace depended on close interaction between two federal

agencies: the FAA and the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD)

The 9/11 Commission report (hereafter, “the report”) indicated

that the military was eventually notified about all the hijackings, but none of

those notifications were made in time to intercept the hijacked aircraft

One of the most glaring examples was demonstrated by the failure

of FAA HQ to request military assistance for the fourth hijacking, that of

Flight 93.

On page 28, the report says, “By 9:34, word of the hijacking had

reached FAA headquarters.” Despite this advance notice, Flight 93

“crashed” in Pennsylvania sometime between 10:03 and 10:07.

FAA HQ got plenty of notice of the four hijacked planes, but

failed to do its job

To put this in perspective, at 9:34 it had been over 30 minutes

since a second airliner had crashed into the World Trade Center (WTC). It

was known that a third plane was hijacked, and it was about to crash into the

Pentagon. Everyone in the country knew we were under a coordinated

terrorist attack via hijacked aircraft because, as of 9:03, mainstream news

stations including CNN had already been televising it.

______________

Denver Post - NORAD

Originally published Sept. 13, 2001

By Mike McPhee

The North American Air Defense Command, which monitors the nation’s airspace

from inside Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado Springs, learned of a plane hijacking

10 minutes before the plane slammed into the World Trade Center.

Capt. Adrian Craig, spokeswoman for NORAD, confirmed the 10-minute warning

but declined to say what action NORAD or the Air Force took once it knew a

plane had been commandeered Tuesday morning.

The Federal Aviation Administration announced Wednesday that the

transponder, a device that alerts air traffic controllers of a plane’s

identification and location, had been turned off on American Airlines Flight

11, the first of two planes to slam into the World Trade Center.

But Craig said it was not the disconnected transponder that alerted NORAD.

She declined to elaborate.

Meanwhile, the Air Force said it is flying fully loaded F-15 and F-16

fighter jets to patrol the skies over the nation’s major metropolitan areas,

including Denver and Colorado Springs. The flights will continue indefinitely.

“Rest assured, they’re equipped and ready to do business,” Craig said.

Numerous Denver residents reported hearing the warplanes overhead late

Tuesday and early Wednesday.

The nearly 29,000 military personnel based in Colorado remained on

heightened alert Wednesday, said officials at Fort Carson Army Base and

Peterson Air Force Base near Colorado Springs.

No troop movements or orders for movements were released to the public.

But a C-5 military cargo jet from Travis Air Force Base in California

arrived at Buckley Air Force Base in Aurora on Wednesday evening to ferry an

urban search-and-rescue team to New York, an Air Force spokesman said.

An Army spokesman, Sgt. 1st Class James Yocum, said troop movements

typically aren’t disclosed until a few hours before the troops leave.

An Air Force spokesman, Staff Sgt. Gino Mattorano, said personnel at

Peterson Air Force Base, Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station, Buckley Air Force

Base in Aurora and the 21st Space Wing remain on “Force Protection and

Information Condition.”

Only mission-essential personnel are reporting for duty until further

notice, he said.

The Air Force Air Mobility Command center at Scott Air Force Base in

Illinois began dispatching military aircraft with supplies and rescue teams to

New York and Washington, D.C., Lt. Col. Brad Peck said.

“We’re moving predominantly medical supplies, humanitarian supplies and

urban search-and-rescue teams,” he said. “We have set up a port mortuary in

Dover, Del., for the victims in the Pentagon. We also are providing aeromedical

evacuation planes to evacuate the wounded out of New York. They are basically

airborne ambulances.”

__________

IN THEIR OWN WORDS (NORAD)

Sept. 7, 2011 —

PETERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Colo. - William Glover is

currently the N2C2 Operations Support Director for the North American Aerospace

Defense Command at Peterson Air Force Base, Colo. On Sept. 11, 2001, he was an

Air Force lieutenant colonel in charge of NORAD Air Defense Operations and was

in the Cheyenne Mountain operations center on that day. He sat down with NORAD

and USNORTHCOM Public Affairs to talk about his experiences on the day of the

attacks.

Q: Tell us a little about your job here at NORAD and USNORTHCOM.

A: My job now is to look after the NORAD equities and the N2C2,

the NORAD and NORTHCOM Command Center. Whenever the general officers here in

the building provide guidance on how the crews need to operate, I transfer that

guidance into checklists and TTPs and that sort of thing so that the crews

understand how we need to operate. On 9/11, my job was Chief, Air Defense

Operations. I worked up at Cheyenne Mountain Operations Center. I was in charge

of the Air Warning Center, which had five crews, and so my job was to maintain

the standardization of operations for the NORAD Ops Center.

Q: Now by what could be called a stroke of luck, everyone you

would need to be in the Mountain on 9/11 was already there the morning of 9/11.

Can you talk about why that was?

A: When people ask me that question, I say, “We were lucky,” you

know, and I get this funny look. We were lucky from the fact that we were in

the middle of a NORAD-wide exercise, and that NORAD-wide exercise had been

going on since the Thursday prior. What that means to us is all the folks in

Building 1470 at the time, all the directorates such as Operations, Logistics,

Security, all those folks were up in the Mountain on an exercise posture. The

lucky part was that these are the same folks that we would bring up in case of

contingencies or in time of going to war. So, in reality, I had all the guys up

into the NORAD Battle Management Center that I needed to conduct the exercise

as well as the contingency operations that happened on 9/11. So what we had to

do was throw the exercise books away and pick up our wartime books and then go

to work.

Q: Another spot of good fortune came from a rather unlikely

source. You mentioned that the Russians did something significant.

A: It’s amazing. At the same time we were conducting this

exercise, the Russians were conducting one of their own. But after the United

Flight 93 went into Shanksville, Penn., the Russians notified us that they were

stopping their exercise because they understood the magnitude of what had

happened to us in the United States. They didn’t want any questions, they

didn’t want us worrying about what they would be doing or entering our Air

Defense Identification Zone. So that was amazing to me, personally, the fact

that they stopped their exercise and, #2, that they told us that they were

going to stop the exercise.

Q: Part of NORAD’s problem on 9/11 was literally the Command’s

outlook. We were looking outward. How did that hamper us and what has been done

since to fix that?

A: It’s important to understand that the job of NORAD at the

time, on 9/11, was to look for threats from outside our countries. We were to

tasked to provide warning of attacks both missile and aircraft as it occurred,

coming into the United States and Canada. And because of that mission, all of

our radars were located along the periphery of the United States and Canada. We

had quite a few radars, numbering over 100 radars looking outward. On 9/11,

what we found out was that we needed radar coverage in the interior of the

United States. And this was demonstrated when the hijackers turned off the

transponders, which is an identification code that the FAA uses to identify

these airliners, we couldn’t see them anymore, so that posed a big problem for

us. We knew the FAA had around 100 long and short range radars in the interior

and we had to figure out how to connect to them. Through some fantastic

innovation by our Continental NORAD Region personnel, we were able to purchase

off-the-shelf software we were able to connect to those interior FAA radars and

basically had the same air picture the FAA had.

Q: And it’s significant when you talk about the number of

aircraft we’re talking about that’s flying at any one time.

A: That number is staggering, especially to the person that

doesn’t realize the number of registered general aviation aircraft and domestic

/ international passenger airliners. On one day – one given day – we have about

2,500 aircraft that fly into the Air Defense Identification Zone of both the

United States and Canada. That ADIZ is located about 200 miles from our shores

and is intended to give us plenty of time to detect the aircraft and determine

its identify. The 2500 number is significant because our NORAD Air Defense

Sectors are tasked with determining the identification of all those aircraft

entering the ADIZ and if we can't, then we may have to launch an armed fighter

to visually identify the aircraft to make sure there is no mal intent. Our

partnership with the FAA helps us tremendously with this task. The FAA shares

flight plan data with us so we can correlate our radar contacts with expected

timings and locations. So we’re looking at all the flight plans of all 2,500 of

those aircraft that are flying in to make sure that they are who they are.

Number two, that’s only aircraft flying into the United States

and Canada. On the interior of the United States, for example, there could be

up to 10,000 aircraft just flying around. Of course, that depends on the

weather and how good the weather is or where they’re flying, but there could be

at least 10,000 airplanes flying at one time.

Q: When people think about the NORAD response, their mind

automatically goes to the fighters coming up alongside the wings. But NATO

stepped up and helped us by contributing another critical asset, and those were

the E-3 Sentries.

A: Yes, that was a much needed asset for us. NATO stepped up and

loaned us seven, we call them E-3’s, Airborne Warning and Control aircraft. And

because we did not have the interior radar coverage inside the U.S., we were

able to fly those E-3’s in certain locations and we could not only monitor the

– the aircraft – of civilian aircraft that were flying around the interior of

the United States, but they could also control our fighter aircraft that we had

flying around over major metropolitan areas.

Q: In the aftermath of the attack, NORAD assets were flying 24/7

and a new operation, Noble Eagle, was started. What is Noble Eagle and why is

it still significant today?

A: That’s true. On the 12th of September, Operation Noble Eagle

(“ONE”) was born. This new threat of civilian airliners being used as a weapon

required a new set of procedures and more assets to defend against. While our

mission did not change, our responsibilities had increased. O.N.E. gives

Commander NORAD the authority to go and investigate and look at these civilian

aircraft that might be attempting to attack the U.S. or Canada.

Q: How has NORAD changed since that day and how have these

changes affected the U.S. and Canada?

A: Our changes have been significant. As I mentioned earlier, we

were looking outward. We were looking for Cold War attacks, we were looking for

bombers, we were looking for air launched cruise missiles, and we were looking

for hijacked aircraft that could be heading toward the U.S. and Canada. But,

since 9/11, we’re now able to monitor aircraft that are flying in the interior

of the United States as well. But we needed more than a radar picture, we

needed a way to talk with our interagency partners in real time. In the months

after the Sep 11 attacks, the FAA developed a communications system called the

domestic events network. The D.E.N. allows us, NORAD, to communicate with the

FAA and other inter agency partners in real time. In the past, typically if

there was an issue onboard an aircraft, whether it was a fight or it was

someone who was drinking too much, that type of thing, those types of incidents

were worked by the airlines and the airline headquarters, and we were not

notified; sometimes the FAA wasn’t notified. But now with this new Domestic

Events Network, the pilots will call in issues that they have on their

aircraft. If they have somebody that’s getting into a fight or somebody that’s

trying to get into the cockpit, he will call his FAA controller who will

forward that information on the DEN and, on the DEN, everybody is listening.

Let’s just say it’s AIRLINE 101. We could dial in the AIRLINE 101 code, look on

our new system, figure out where that aircraft is in relationship to air bases,

and decide if we needed to scramble fighters or we needed to monitor that

aircraft. We didn’t have this prior to 9/11. Now we do, we have almost near

instantaneous situational awareness of where these aircraft are and what their

problem is. It is important to note that it is the synergy of all of our

interagency partners that make the skies safe to fly. It is not just NORAD.

Q: Now you’ve made it a point to go out and talk about 9/11 at

universities. What do you tell these students and why do you do this?

A: Well, both personal reasons and – and professional reasons.

I’m asked to go speak at Denver University. They want me to talk about my

personal observations of 9/11, and I’m happy to do that. They want me to talk

about how NORAD has improved since that point. For my personal observations, I

just like to point out that, on 9/11, we had about 50 individuals working in

the NORAD Battle Management Center in Cheyenne Mountain and watching those

individuals react to the airliners impacting the World Trade Center is

something I will never forget. I saw a full gamut of emotions in that room. I

saw some folks that were normally talkative as quiet as can be. I saw people

that normally don’t talk just start to be jittery, walk around, not knowing

what to do with themselves. I saw people reacting that normally don’t react

that particular way. It was amazing to me to see that. But what I did see was a

team coming together. They were professionals...They went to work to defend

their nation and they were able to work together as a team. As far as speaking

to the graduate level course at Denver University, on my last lecture, I looked

around the audience and I saw kids in there that I imagined to be somewhere

around 12 years old on 9/11. And so my thought was, “I hope we don’t forget.” I

hope we don’t forget what happened on 9/11 and how we have to work as a team,

not only as a team in that room on 9/11, but as a team to include our

interagency partners. And to that end, we have developed a great working

relationship with partners such as FAA, we’ve developed a great working

relationship with TSA and all those folks that support this nation's defense.

Because really, NORAD should be considered the last resort. If all of our

partners have done their job, then there’s no need for us to get airborne and

be prepared to intervene in a hijacked aircraft. So my point there to these

students is: It’s teamwork. It’s on everybody working together with their own

piece of the pie to make the nation secure. And that’s what I’m trying to teach

them.

Q: What stands out the most about that day to you?

A: Everybody has their own memories of that day. I will never

forget driving up to Cheyenne Mountain that day and I remember looking out at

the weather, and it was the most beautiful day I’d ever seen. There wasn’t a

cloud in the sky, and I was thinking, “Well, I sure don’t want to be at work

today.” And getting in and going and riding on the bus a third of a mile into

the Mountain and getting off the bus and walking into the NORAD Battle

Management Center to assume what I thought was going to be a normal day, which

changed almost immediately. But what stands out, again, is the ability of 50

individuals to come together as a team and – and do their job and I’ve got to

tell you, they didn’t want to go home. These folks were in there early, like at

6:00, and they didn’t want to go home. Our Commander at the time stuck his

noggin into the room and said, “Hey, we’ve gotta send these guys home because I

need ‘em fresh for tomorrow.” And that’s one of the thoughts that stands out to

me. Nobody wanted to go home. They wanted to get the job done, but they had to

be told to go home.

Q: It’s 10 years later. Osama bin Laden is dead. Al Qaeda, the

argument is, is in ruins. Do you think the changes that have come to NORAD and

the United States security apparatus, do you think those are still necessary?

A: Oh, most definitely. The attacks on 9/11, that was a slap. That

was a slap to us. That was an attention getter for us that we had to be more

aware of what was going on in the air. We had to be more aware of people out

there that are that want to kill Americans. They want to kill, you know,

Canadians as well. And so I think what we’ve done in building relationships

with our federal interagency partners, building relationships with the local

law enforcement, is only for the better. I know that going through the airport

and having to go through all the TSA security is sometimes a pain in the

you-know-what, but I’ve gotta tell you we need it. We have to have that done if

we want to keep the skies secure and – and safer not only for yourself, but for

your family.

Q: If you could leave this interview with one message to

Americans and Canadians who fall under the NORAD umbrella, what would it be?

A: Maintain your vigilance. Maintain your professionalism. We’re

here for a reason. We’ve evolved over the last 10 years to develop into an air

defense organization that has a job not only in defending from attacks from the

outside, but also for defending asymmetric threats like we – that occurred on

9/11. Just maintain your professionalism and I think everything will work out.

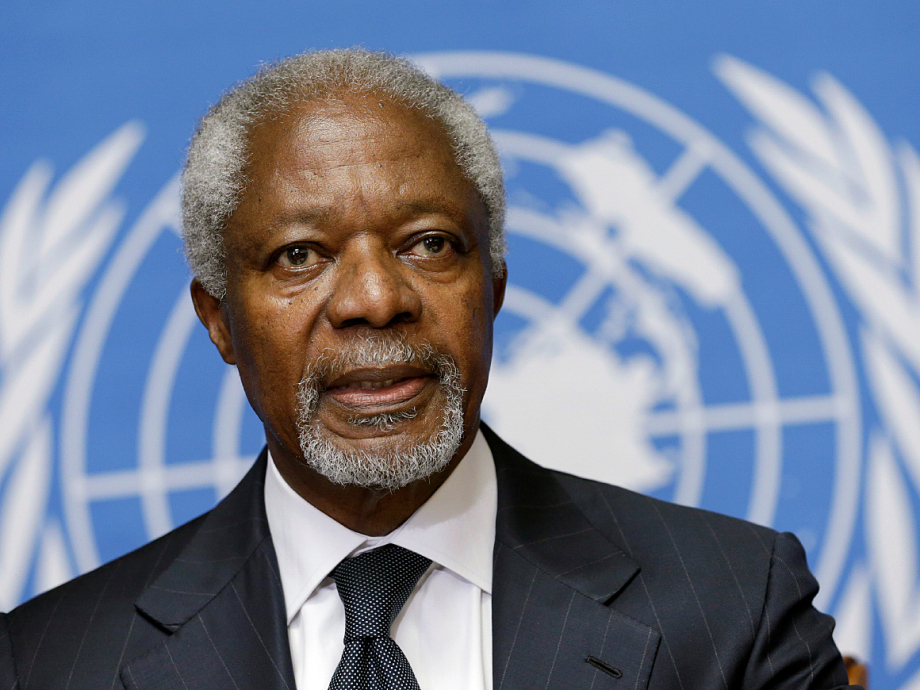

Dr Kofi Annan served as the seventh Secretary-General of the UN

Dr Kofi Annan served as the seventh Secretary-General of the UN Dr Kofi Annan's wife, Nane Maria Annan, lays a wreath during the burial service held at the Military Cemetery at Burma Camp in Accra

Dr Kofi Annan's wife, Nane Maria Annan, lays a wreath during the burial service held at the Military Cemetery at Burma Camp in Accra Dr Kofi Annan's wife, Nane Maria Annan, lays a wreath during the burial service held at the Military Cemetery at Burma Camp in Accra

Dr Kofi Annan's wife, Nane Maria Annan, lays a wreath during the burial service held at the Military Cemetery at Burma Camp in Accra Honour guards carry the flag-draped casket of Kofi Annan

Honour guards carry the flag-draped casket of Kofi Annan